I am writing this blog not only as a victim but also as a criminologist with a passion for victimology. Secondary victimization refers to the harm that occurs after the initial incident due to inappropriate responses from institutions such as the police and justice system, or from the victim’s social environment. In other words, the victim is revictimized. This can lead to feelings of being unrecognized or unfairly treated, ultimately hindering the recovery from the original trauma.

From my own experience, I know that secondary victimization is a form of secondary trauma, requiring the victim to go through an additional process of healing on top of the original trauma. In my case, this secondary victimization occurred on three levels – by the police, the judicial system and my social circle. This triple victimization exacerbated the mild depression I had been experiencing since 2020, during the COVID pandemic – though unrelated to it – turning it into chronic and intensified suffering. Today, I realize that if these three levels had treated me just slightly differently, my recovery might not have started from such a deep, dark place. Perhaps I wouldn’t have experienced the worst of the worst, or healing might have happened faster than it ultimately did. This blog is a call for accountability from the environment surrounding victims.

Three Examples of Secondary Victimization

It is impossible to discuss secondary victimization without first addressing the primary harm. Without hesitation, I write it here: I was a victim of grooming and sexual abuse between the ages of 14 and 15. I choose the term “victim” despite the common belief that it carries a negative and stereotypical connotation. Some prefer to call themselves “survivors” to reclaim their strength, as the term “victim” often evokes passivity and suffering. This interpretation is deeply rooted in Christian symbolism – where a victim was seen as a sacrificial offering, akin to the suffering of Christ, inspiring pity. I understand why many reject the idea of being seen as weak or pitiful.

However, I oppose the survivor movement, and my stance is shaped entirely by my experience of secondary victimization.

Example 1

The Failure of the Police System

In 2020, after sharing my full story for the first time – without minimizing or omitting details out of shame – with my psychologist, I felt a strong urge to report the abuse to the police. Looking back, I believe this urge stemmed from a fight response, perhaps similar to those who prefer the term “survivor” over “victim.” It was an impulse to assert my strength – not to passively endure suffering but to take action against the injustice done to me.

My psychologist initially warned me not to rush this process and asked me critically what I hoped to achieve by filing a report – not to discourage me, but to prepare me for potential secondary victimization within the justice system. However, once I am convinced of something, I find it difficult to let go. When I decide on action, it must happen immediately. That’s exactly how I felt. The report had to be filed right away.

I researched the procedure for reporting sexual offenses. On the website of my local police department, I read that I could make an appointment, after which a specialized officer in sexual offenses would be assigned to conduct the interview.

There were six police errors.

1) So, I made the call. A woman from the police department answered. She sounded friendly but insisted that I didn’t need an appointment.

Instead, she advised me to come to the station after 9 PM, claiming it wouldn’t be busy, and I could file my report immediately. She reassured me that all officers were trained to handle these types of cases, so there was no need for a specialized officer. Her confidence convinced me.

On October 18, 2021, I arrived at the police station without an appointment. Before me, another citizen was filing a report about a car break-in, so I had to wait for about an hour. My interview finally began around 10 PM…

The officer assigned to me was a man. No one asked if I was comfortable with that. He also asked if I minded keeping the door open during the interview. In all honesty, I found it uncomfortable – I could hear voices and movement in the hallway, which made me hesitant to speak freely – but I was too nervous to refuse.

That said, the officer maintained a calm demeanor. Looking back, the words that come to mind are: objective, mature, professional, honest and composed. I didn’t feel judged, even though I tend to be sensitive to rejection.

However, he was not a specialist. I wasn’t able to add the nuances I wanted to my statement. Understandably, I was asked if force had been used and if the sexual activities had occurred against my will. I could only answer truthfully – there was no force or threats. I tried to clarify that the situation was far more complex than that. While the officer assured me he understood, I wished I had explained it more. But perhaps that wasn’t necessary. Maybe the police understood enough?

2) “What I did not feel, however, was victim support or aftercare. I received no acknowledgment.”

After the interview, the officer warned me about the potential for secondary harm. He said he didn’t expect much legal action to result from my report. Rationally, I understand why the police avoid giving victims false hope. It’s important to paint a realistic picture.

But emotionally, it was damaging. Not just because I was warned once about the – seemingly – futility of my report. What truly hurt was that, in every single interaction I had with the police afterward, I kept hearing those same words over and over.

The police are not judges, are they? And I am not slow to understand.

3) “Yet the constant discouragement of victims, rather than empowering them, is also a form of secondary victimization.”

After my report, my case was transferred to the police department in my hometown, where the incidents had taken place. There, an officer named Jos/Jozef, who claimed to work exclusively on sexual offense cases, took charge of “my story.” I say “my story” because the man never asked to meet me. He only asked a few brief questions over the phone and never initiated a real conversation.

4) Unlike the first officer, the words that come to mind for him are: crude, dismissive, inappropriate, incompetent, and entirely unfit for his role in handling sexual offenses. He made tasteless comments in a failed attempt to offer me some sense of justice.

For example, in yet another effort to convince me that my report would lead to nothing, he said I should find “some comfort” in the fact that my abuser had to confess his adultery to his wife. This officer equated my abuse to an affair between consenting adults. The relationship problems my abuser faced as a result of my report were, in his eyes, a kind of “punishment” that should bring me solace. That was also how I first learned that my abuser was (still) married…

Additionally, over the phone, the officer asked me about the location of the hotel where the abuse took place. I simply referred to it as “a hotel” because, at 14, I had no concept of what a “meeting hotel” was. In my mind, it was just a hotel. As an adult, I later understood that such hotels had a different purpose. But the officer found it necessary to correct my vocabulary – mockingly: “Hotel? You mean a meeting hotel. That’s not a real hotel, you know.”

After my abuser was questioned, the officer informed me. He wasn’t allowed to disclose much about the interrogation. However, he did advise me that I needed concrete proof that my abuser knew my real age. My abuser had claimed that he thought I was “already studying” at the time – implying he believed I was 18 or older.

The officer also advised me to review my case file after it was closed by the prosecution. “Although,” he warned, “there may be things in there that the perpetrator said about you that will make you angry.”

5) With the overwhelming thoughts – “I have to prove the impossible, my abuser is lying, I have already lost” – and the fear of “What on earth has he said about me?” – the officer left me to fend for myself.

My case was ultimately transferred to the prosecution, where it remained in limbo for months.

6) When I tried to file a complaint about how the police had handled my case, I found out it wasn’t possible.

Example 2:

And Countless Judicial Errors?

In 2019, Belgium abolished the statute of limitations for sexual offenses against minors. This stands in stark contrast to the fact that the prosecution will, in many cases, technically dismiss cases like mine – choosing not to prosecute due to the age of the case and, consequently, a lack of evidence (for example, in my case: no proof that my abuser could have known I was a minor?!). Yet, the statute of limitations was abolished precisely because society recognized that it often takes years before a victim can break their silence.

On April 1, 2022, I received a letter from the Public Prosecutor. It was a notification about a free and judicially independent mediation service: Moderator. The letter explained:

“The purpose of mediation is to actively involve both the victim and the suspect in the further handling of the case. It also provides the parties with a way to communicate about the facts and their consequences, helping them find a way to cope with them … Mediation does not replace the traditional judicial process but can serve as a meaningful addition to it.”

The procedure is thus intended to operate independently of the judicial process. All information shared during mediation remains confidential and cannot be used in legal arguments. In short, mediation is supposed to restore a sense of autonomy and voice to both victim and perpetrator, as the legal system primarily takes that away.

According to Google, ‘mediation’ refers to conflict resolution. I personally associated it with intervention, compromise, mutual fault, a middle ground.

So, the word ‘mediation’ immediately gave me, as a victim, the feeling that I somehow bore responsibility for my victimhood. If Moderator’s mediation is truly what it claims to be, then I consider the terminology emotionally misleading. I had expected the dismissal of my case – I had braced myself for it. Mediation, however, I had not expected. It felt like another slap in the face, as if society was telling me that I needed to accommodate my perpetrator or understand his situation. Initially, I refused the voluntary offer. That is, until Moderator contacted me themselves – because my perpetrator had accepted it.

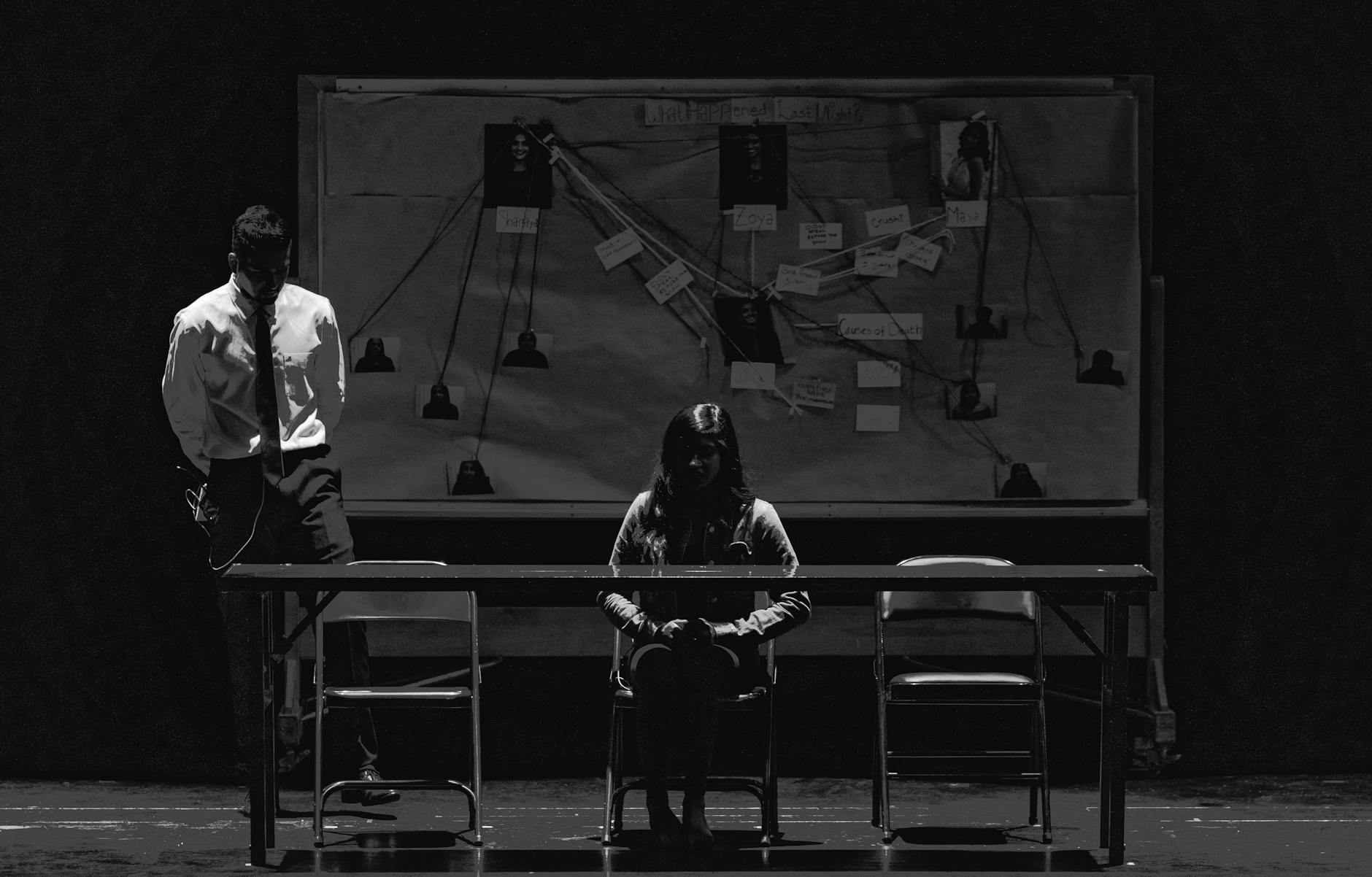

My mediator did provide some nuance. She clarified once again that mediation through Moderator did not determine how the legal proceedings would conclude. She also made the roles of both parties clear: the victim had the right to take their rightful place in the victim’s chair, and the perpetrator in the perpetrator’s chair. Her goal was to explore what I needed to facilitate some form of healing and to help the perpetrator take responsibility.

For me, that meant:

“When my perpetrator stated that he felt I could consent because I was so “mature” – even though he knew I was a minor and was aware of the law – then I asked society to stand with me in sending the message that this was denial of his wrongdoing. That he was refusing to take responsibility. That he was attempting to justify his actions based on his own fabricated perceptions rather than acknowledging his guilt. That, beyond legality, his actions were also morally wrong.”

But Moderator could not support me in that. After all, Moderator was “neutral.” My mediator could communicate the message, “Society and the justice system see it differently,” to my perpetrator – and she did – but during a direct meeting between perpetrator and victim, she could not back me up. She could not advocate for me, nor explain to him that his claim about my supposed maturity was actually a way of denying the facts and the harm caused. Instead, she clung to the studied phrase: “Society and justice see it differently.”

Well, to me, there is no more formal or detached way to call someone to account. That phrase sounds to me like saying, “Objectively, there’s a law on paper, but emotionally, I completely agree with what you did.” It feels like saying, “I stand outside of the society that sees it that way.” And I wonder: how effective is such a message in actually reaching a perpetrator?

Sometimes, it feels as if the mediator’s impartiality primarily benefits the perpetrator. In vain, I asked my mediator whether she, too, was part of ‘society.’ She did not answer.

“Once again, the victim stands alone“

So I must conclude: in Moderator’s mediation, the victim is once again left standing alone.

And how independent is the legal outcome from the mediation process, and vice versa, when the Public Prosecutor is the one tasked with informing us about Moderator’s existence? How independent is the legal outcome when mediation’s stated goal is to “actively involve the victim and perpetrator in the further handling of the case”?

I put these questions to my judicial assistant. She explained that Moderator’s mediation is often proposed in cases where the justice system is considering dismissal. Mediation would then serve as a way to give something back to the victim – a sign that they are believed, that they are taken seriously.

Yet, based on my experience with Moderator’s mediation, it feels more like a way for the justice system to soothe its own conscience. Mediation becomes a way to acknowledge failure while telling the victim that they must now resolve it themselves.

“For now, mediation feels like nothing more than a tragic breadcrumb that justice strategically tosses when the system fails.“

Example 3

The Silence of Those Who Should Care

This blog post has already become too long and I have little energy left to write about the final example. Perhaps that’s also because it is the most painful one.

The last lifeline is the people closest to you, those who can keep you from falling into the deepest darkness. But even the social circle can fail in supporting a victim. When I first told two carefully chosen friends that I had “filed a police report” (which was already a rather loaded statement), they asked no questions – perhaps out of fear. But isn’t it strange not to ask anything when a friend tells you she has been to the police?

During my suicide attempts, there was some initial response, but once I was discharged from the hospital, I was quickly forgotten – everything was “normal” again.

When I confronted my family, especially my parents, about their neglectful behavior during my childhood and teenage years, they became angry. It was, in fact, the first time they learned that I had been abused, yet instead of offering support, they blamed me – for holding them accountable for failing to notice my struggles when I was their child. This despite the fact that they knew I self-harmed, that I ran away from home as a child, and so much more examples that should have opened their eyes for my wellbeing.

My partner was barely present after I reported my case. He struggled emotionally and offered only limited support for my decisions. Fortunately, that has since changed.

Because of all these people, I say today:

I am a victim – not a survivor – despite your collective denial. I have the right to claim this label.

Plaats een reactie